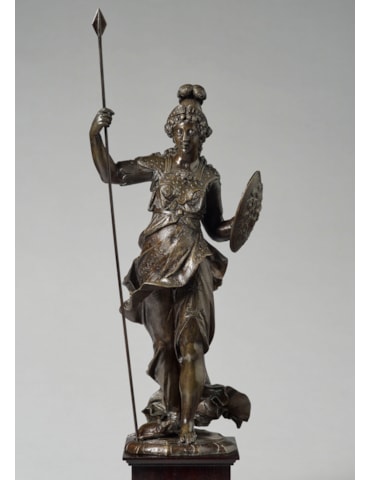

Romano Alberti

Sansepolcro fl. 1521 - 1568

Infant Martyr Saint

Polychrome statue of stucco and papier mâché, constructed around a wood core.

Overall height, excluding halo: 83 cm / 32¾ in

Height of integral base: 8 cm / 3⅛ in

Overall height, excluding halo: 83 cm / 32¾ in

Height of integral base: 8 cm / 3⅛ in

ENQUIRIES

+44 (0)20 7259 0707

Exhibited: Sculture “da vestire”. Nero Alberti da Sansepolcro e la produzione di manichini lignei in una bottega del Cinquecento, Umbertide, Museo di Santa Croce, 11 June – 6 November 2005, pp. 179-180, no. 15.

Condition and facture: The sculpture is in good condition and the polychrome surface is in the main original. The paint on his upper arms and torso may be of a later date. The construction of this figure1 is typical of wooden sculptures by Romano Alberti and his circle.

This figure is one of a number of devotional images that are similarly constructed in stucco and wood and are now known to have been produced in the workshop of Romano Alberti, called “il Nero”. It compares closely with other fine examples of Alberti’s production, and the similarities with the Infant St John the Baptist in the Museo Bardini are so close that they must surely be from the same hand.2 In the spontaneity of the modelling and the high degree of naturalism, this lively sculpture also closely resembles the Infant Christ Blessing in a private collection.3

Only with the recent emergence of the artistic personality of Romano Alberti has it become possible to associate those works formerly attributed to the “Maestro di Magione” with him.4 Among the group of sculptures formerly ascribed to the Maestro di Magione and now to Romano Alberti was a San Rocco in Pergola (Museo dei Bronzi dorati e della città di Pergola) that relates directly to another statue of the same subject (Umbertide, chiesa di Santa Croce)5. The latter, which bears some of the stylistic traits of Alberti, is inscribed with the date 1527, the year of a plague in Umbertide, and the sculpture is known to have been in the church of San Francesco at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1523, Alberti had been commissioned to make a “simulacrum divi Antonii de Padua” for the same church.6

Comparison between Alberti’s Corpus in Santa Maria delle Grazie al Rivaio, Castiglion Fiorentino, made in 1562,7 and known works from earlier in his life, such as the ceiling carvings in Palazzo Vitellli, show that the enduring tradition of late fifteenth-century Florentine wood-carving continued to influence him throughout his career. We can therefore expect a high degree of consistency of style in his sculpture.8 According to Christiane Klapisch-Zuber (1988),9 sculptures of this type were often presented as marriage gifts either to young couples or to young girls destined to enter a convent. Such figures were generally placed on a domestic altar or in a tabernacle and were provided with a wardrobe of ceremonial clothes. So that they might be dressed, the arms of the ‘mannequins’ were detachable.

Although the earlier history of the present Infant Martyr Saint is not known, it could also have served as a votive image at a church altar, such as that of a devotional confraternity, and during festivals may have been paraded through the town. The precise identity of the Saint is not known, but suggestions have included: San Simonino, a boy from Trent whose murder, discovered on Easter Sunday 1475, was blamed on Jews; and San Felicissimo, an Umbrian boy who became a hermit having been disowned by his parents for giving their cow away to the poor.10

Biography:

Romano Alberti 11 was a member of a prolific yet little-known family of artists from Sansepolcro. The diaries of his nephew, Alberto (1525-1598), a sculptor, painter, military engineer and cartographer, are an important art historical source and form part of the Alberti archive in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.12 They contain only two mentions of Romano. The first records that he was in debt by 22 florints and the second concerns his death: “Zeeio Nero murì a dì 8 dicembre 1568.13

The earliest known documentary reference to Romano Alberti is the certificate of his marriage on 4 December 1521 to Giuditta, daughter of Bartolomeo di Giuliano di Santi del Mancino. Two years later came a commission from the Confraternity of Santa Croce for various wood furnishings for the choir and high altar of the church of San Lorenzo a Sansepolcro, on which he was to collaborate with Schiatto Schiatti. From a document of May 1535 we learn that he was employed to supply temporary decoration and fittings for the purposes of sacre rappresentazioni, in this case for the celebration of the feast of Corpus Domini at Santa Maria della Misericordia in Sansepolcro. His contract to decorate the organ case in the Cathedral of Arezzo, in which he was described as “maestro d’intaglio di legniame”, was drawn up in the same year. The organ case survives in situ. Other surviving documented works by Romano include wood carvings for the ceilings in the Palazzo Vitelli a San Giacomo in Castello. A bust of Sant’Antonio da Padova in the sacristy of San Francesco, Umbertide has recently been linked with the commission for Romano Alberti to make “simulacrum divi Antonii de Padua” for the church of San Francesco.14

Alberto Alberti, Romano’s nephew, is known to have been running a second studio specialising in wood-carving at the same time as - and only a short distance from - his uncle’s. Despite fierce family rivalry, it was not until Romano’s death in 1568 that Alberto moved to Rome.

1. For x-rays and technical analysis of comparable figures, see E. Signorini & G. Signorini, “Diagnostica radiological con TC elicoidale multistrato” in Scultura “da vestire”. Nero Alberti da Sansepolcro e la produzione di manichini lignei in una bottega del Cinquecento, exh. cat. ed. C. Galassi, Umbertide, Museo di Santa Croce, 11 June – 6 November 2005, pp. 115-124.

2. C. Bellandi in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 173-174, no. 12; see also B. Santi in E. N. Lusanna & L. Faedo, Il Museo Bardini a Firenze. II. Le Sculture, p. 285, no. 291, pl. 332 (inv. no. 1089).

3. A. Bellandi in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 177-178, no. 14. 4. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro" in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, pp. 24-27. For the Maestro di Magione, see E. Neri Lusanna, “Tra arte e devozione: la tradizione dei manichini lignei nella scultura umbro-marchigiana della prima metà del Cinquecento” in G. B. Fidanza (ed.), Scultura e arredo in legno fra Marche e Umbria,. Atti del primo convegno, Pergola, 24-25 October 1997, Perugia, 1999, pp. 23-30. 5. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, pp. 24-25, figs 7-8. See also see B. Montevecchi, “I Legni di Pergola” in Scultura e arredo in legno fra Marche e Umbria 1997, p. 126.

6. See also Biographical Note, above.

7. L. Fornasari in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 185-186, no.17.

8. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, p. 27, and, for work at the Palazzo Vitelli, pp. 21-23. Some of the figures included in the present exhibition in Umbertide are derivative works and by other hands. It would be very reasonable to expect a number of rival workshops working in the wake of Alberti in his locality.

9. C. Klapisch-Zuber, La famiglia e le donne nel Rinascimento a Firenze, Bari, 1988, cited by C. Galassi in Nero Alberti 2005, p. 179.

10. C. Galassi in Nero Alberti 2005, p. 179.

11. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, especially pp. 15-27.

12. Grove Dictionary of Art Online [author not specified], accessed 16 June 2005, http://www.groveart.com.

13. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, especially pp. 15-27, p. 16.

14. Ibid, pp. 15-104, pp. 23-24, fig. 5.

Condition and facture: The sculpture is in good condition and the polychrome surface is in the main original. The paint on his upper arms and torso may be of a later date. The construction of this figure1 is typical of wooden sculptures by Romano Alberti and his circle.

This figure is one of a number of devotional images that are similarly constructed in stucco and wood and are now known to have been produced in the workshop of Romano Alberti, called “il Nero”. It compares closely with other fine examples of Alberti’s production, and the similarities with the Infant St John the Baptist in the Museo Bardini are so close that they must surely be from the same hand.2 In the spontaneity of the modelling and the high degree of naturalism, this lively sculpture also closely resembles the Infant Christ Blessing in a private collection.3

Only with the recent emergence of the artistic personality of Romano Alberti has it become possible to associate those works formerly attributed to the “Maestro di Magione” with him.4 Among the group of sculptures formerly ascribed to the Maestro di Magione and now to Romano Alberti was a San Rocco in Pergola (Museo dei Bronzi dorati e della città di Pergola) that relates directly to another statue of the same subject (Umbertide, chiesa di Santa Croce)5. The latter, which bears some of the stylistic traits of Alberti, is inscribed with the date 1527, the year of a plague in Umbertide, and the sculpture is known to have been in the church of San Francesco at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1523, Alberti had been commissioned to make a “simulacrum divi Antonii de Padua” for the same church.6

Comparison between Alberti’s Corpus in Santa Maria delle Grazie al Rivaio, Castiglion Fiorentino, made in 1562,7 and known works from earlier in his life, such as the ceiling carvings in Palazzo Vitellli, show that the enduring tradition of late fifteenth-century Florentine wood-carving continued to influence him throughout his career. We can therefore expect a high degree of consistency of style in his sculpture.8 According to Christiane Klapisch-Zuber (1988),9 sculptures of this type were often presented as marriage gifts either to young couples or to young girls destined to enter a convent. Such figures were generally placed on a domestic altar or in a tabernacle and were provided with a wardrobe of ceremonial clothes. So that they might be dressed, the arms of the ‘mannequins’ were detachable.

Although the earlier history of the present Infant Martyr Saint is not known, it could also have served as a votive image at a church altar, such as that of a devotional confraternity, and during festivals may have been paraded through the town. The precise identity of the Saint is not known, but suggestions have included: San Simonino, a boy from Trent whose murder, discovered on Easter Sunday 1475, was blamed on Jews; and San Felicissimo, an Umbrian boy who became a hermit having been disowned by his parents for giving their cow away to the poor.10

Biography:

Romano Alberti 11 was a member of a prolific yet little-known family of artists from Sansepolcro. The diaries of his nephew, Alberto (1525-1598), a sculptor, painter, military engineer and cartographer, are an important art historical source and form part of the Alberti archive in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.12 They contain only two mentions of Romano. The first records that he was in debt by 22 florints and the second concerns his death: “Zeeio Nero murì a dì 8 dicembre 1568.13

The earliest known documentary reference to Romano Alberti is the certificate of his marriage on 4 December 1521 to Giuditta, daughter of Bartolomeo di Giuliano di Santi del Mancino. Two years later came a commission from the Confraternity of Santa Croce for various wood furnishings for the choir and high altar of the church of San Lorenzo a Sansepolcro, on which he was to collaborate with Schiatto Schiatti. From a document of May 1535 we learn that he was employed to supply temporary decoration and fittings for the purposes of sacre rappresentazioni, in this case for the celebration of the feast of Corpus Domini at Santa Maria della Misericordia in Sansepolcro. His contract to decorate the organ case in the Cathedral of Arezzo, in which he was described as “maestro d’intaglio di legniame”, was drawn up in the same year. The organ case survives in situ. Other surviving documented works by Romano include wood carvings for the ceilings in the Palazzo Vitelli a San Giacomo in Castello. A bust of Sant’Antonio da Padova in the sacristy of San Francesco, Umbertide has recently been linked with the commission for Romano Alberti to make “simulacrum divi Antonii de Padua” for the church of San Francesco.14

Alberto Alberti, Romano’s nephew, is known to have been running a second studio specialising in wood-carving at the same time as - and only a short distance from - his uncle’s. Despite fierce family rivalry, it was not until Romano’s death in 1568 that Alberto moved to Rome.

1. For x-rays and technical analysis of comparable figures, see E. Signorini & G. Signorini, “Diagnostica radiological con TC elicoidale multistrato” in Scultura “da vestire”. Nero Alberti da Sansepolcro e la produzione di manichini lignei in una bottega del Cinquecento, exh. cat. ed. C. Galassi, Umbertide, Museo di Santa Croce, 11 June – 6 November 2005, pp. 115-124.

2. C. Bellandi in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 173-174, no. 12; see also B. Santi in E. N. Lusanna & L. Faedo, Il Museo Bardini a Firenze. II. Le Sculture, p. 285, no. 291, pl. 332 (inv. no. 1089).

3. A. Bellandi in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 177-178, no. 14. 4. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro" in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, pp. 24-27. For the Maestro di Magione, see E. Neri Lusanna, “Tra arte e devozione: la tradizione dei manichini lignei nella scultura umbro-marchigiana della prima metà del Cinquecento” in G. B. Fidanza (ed.), Scultura e arredo in legno fra Marche e Umbria,. Atti del primo convegno, Pergola, 24-25 October 1997, Perugia, 1999, pp. 23-30. 5. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, pp. 24-25, figs 7-8. See also see B. Montevecchi, “I Legni di Pergola” in Scultura e arredo in legno fra Marche e Umbria 1997, p. 126.

6. See also Biographical Note, above.

7. L. Fornasari in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 185-186, no.17.

8. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, p. 27, and, for work at the Palazzo Vitelli, pp. 21-23. Some of the figures included in the present exhibition in Umbertide are derivative works and by other hands. It would be very reasonable to expect a number of rival workshops working in the wake of Alberti in his locality.

9. C. Klapisch-Zuber, La famiglia e le donne nel Rinascimento a Firenze, Bari, 1988, cited by C. Galassi in Nero Alberti 2005, p. 179.

10. C. Galassi in Nero Alberti 2005, p. 179.

11. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, especially pp. 15-27.

12. Grove Dictionary of Art Online [author not specified], accessed 16 June 2005, http://www.groveart.com.

13. C. Galassi, “Arte e serialità nella bottega di Nero Alberti a Sansepolcro” in Nero Alberti 2005, pp. 15-104, especially pp. 15-27, p. 16.

14. Ibid, pp. 15-104, pp. 23-24, fig. 5.