Carlo Monaldi

Rome 1683 - Rome 1760

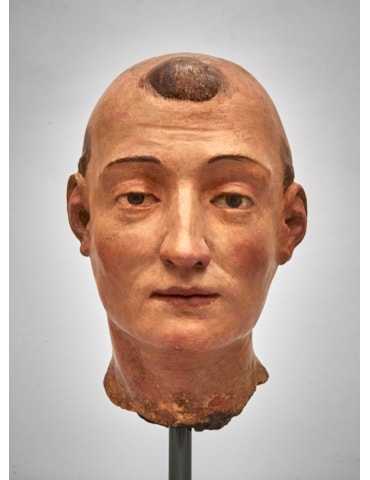

San Francesco da Paola

Terracotta relief, with original gilt bronzed surface and gilt wood frame

Dimensions of relief: 57 x 37.5 cm (22½ x 14¾ in)

including gilt wood frame: 73 x 54.5 cm (28¾ x 21½ in)

Dimensions of relief: 57 x 37.5 cm (22½ x 14¾ in)

including gilt wood frame: 73 x 54.5 cm (28¾ x 21½ in)

ENQUIRIES

+44 (0)20 7259 0707

Condition: The modelling of the terracotta is exceptionally fresh and the gilt bronze finish applied to the surface is original. There are a few minor losses to extremities and San Francesco is lacking his left hand.

It is evident from the treatment of the surface, both in terms of the sharpness of the modelling and the deliberate creation of an apparently-aged bronze surface, that the relief was originally intended to look like bronze; in fact, it resembles gilt bronze. This has been achieved by preparing the surface with a ground of pale yellow ochre paint and brushing on a fine layer of bronze powder in an oil mordant, on top of which darker areas have been applied to give the impression of a rubbed patina.1 Bronzing or otherwise colouring terracottas had been common practice since the fifteenth century, but most have had their original surfaces ‘restored’ to conform to the aesthetic sensibilities of later generations.

The composition of this relief is similar to a terracotta relief in the Galleria dell’Accademia Nazionale di San Luca in Rome, which was attributed to Maini in an inventory of 1830. Jennifer Montagu has shown that Maini’s rectangular relief was adapted as a lunette for the chapel of San Francesco in the right transept of San Andrea delle Fratte (begun 1726; consecrated March 1736).2 It is not clear to which project the present relief relates, but there were other churches dedicated to the saint in Rome, for instance San Francesco di Paola ai Monti.

San Francesco da Paola takes his name from the village in Calabria where he was born in 1416. His parents were Jacopo and Vienna Martotilla. He entered the Franciscan friary of San Marco in Paola as a thirteen-year-old and went on a pilgrimage to Assisi and Rome the following year. On his return to Paola he became a hermit, spending five years in isolation. In 1436, he and two followers established a community which became known as the order of the hermits of St Francis of Assisi. The rule for the order was austere, with an emphasis on penance, humility and charitable works; they eschewed meat. Learning was not considered particularly important and each community usually included only one priest. The order received approval from the Holy See in 1474 and in 1492 Francesco directed that his followers call themselves the Order of Minimi. His reputation for miracle-working and prophecy was such that pope Sixtus IV responded to the request of Louis XI of France in 1483 that Francesco care for him on his deathbed. He remained in France for the rest of his life and Charles VIII and Louis XII endowed monasteries for his order in Pléssis-lez-Tours and Amboise. He died in 1507 at Pléssis. Under the papacy of Leo X, he was beatified on 7 July 1513 and canonized on 1 May 1519.

The prayer book held by the seated angel is open at a page inscribed with part of the collect (short prayer) for his feast day on 2 April 3 – OREMUS deus humilium celsitudo, qui Bea tum Franciscum Confessorem san= ctorum gloria Mast Mi t

Biographical Note:

Monaldi 4 attended the art school run by the Accademia di San Luca in Rome and won prizes in the competitions held there in 1705, 1707, 1709 and 1711. In June 1730 he was admitted to the Academy on condition that he resign from the carpenters’ guild and not serve in public as an artilleryman, i.e. he would be restricted to the Castel Sant’Angelo. Monaldi was appointed by the Academy to supervise the transfer of alcuni gessi (plaster models) which Bernardino Cametti had bequeathed to it in his will.5 He negotiated the rights to all the overspill from a large travertine fountain celebrating Venice’s dominion over the sea, which he had been contracted to make in June 1729 for Palazzo Venezia, Rome, and he used the surplus water to set up washhouses. His earliest marble, a statue of St Francis in the apse of St Peter’s, dates from 1720, and for the same basilica he carved Humility and St Cajetan (latter dated 1730). In the early 1730s he worked on several statues for the basilica built by King Juan V at Mafra in Portugal – three over-lifesize statues of Sts Vincent, Elias and Philip Neri and colossal statues for the exterior of Sts Sebastian and Theresa (latter dated 1731, all five signed).

There followed marble statues of Abundance and Magnificence (1736) for the monument to Clement XII in S. Giovanni in Laterano, Rome; a Pope (1743) in travertine for Santa Maria Maggiore and six stucco reliefs of apostles in the nave of San Marco.

1. We are grateful to Carol Galvin, conservator of sculpture, for providing this visual analysis of the bronzed surface. She has seen other Roman terracottas of the same period with similarly-treated surfaces.

2. J. Montagu in Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, exh. cat. ed. E. P. Bowron & J. J. Rishel, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 16 March – 28 May 2000 & Houston, Museum of Fine Arts, 25 June – 17 September 2000, no. 133, p. 261; V. Golzio, Le terrecotte della R. Accademia di S. Luca, Rome, 1933, pp. 33 & 51, pl. xv. See also J. Montagu, “Giovanni Battista Maini’s role in two sculptural projects: the evidence of the drawings”, “Essays in Memory of Jacob Bean (1923-1992)”, Master Drawings, vol. 31, no. 4, 1993, pp. 454-463, p. 457.

3. Deus, humilium celsitudo, qui beatum Franciscum sanctorum tuorum gloria sublimasti, tribue, quaesumus, ut, eius meritis et exemplo, promissa humilibus praemia feliciter consequamur. We are grateful to Michael Walsh, Theology Librarian, Heythrop College (University of London), for explaining and elaborating these lines in Latin. They may date from the second decade of the sixteenth century, when Francis was beatified and canonised.

4. R. Enggass, Early Eighteenth-century Sculpture in Rome, 1976, pp. 183-188, pls. 188-210

5. Enggass 1976, p. 153.

It is evident from the treatment of the surface, both in terms of the sharpness of the modelling and the deliberate creation of an apparently-aged bronze surface, that the relief was originally intended to look like bronze; in fact, it resembles gilt bronze. This has been achieved by preparing the surface with a ground of pale yellow ochre paint and brushing on a fine layer of bronze powder in an oil mordant, on top of which darker areas have been applied to give the impression of a rubbed patina.1 Bronzing or otherwise colouring terracottas had been common practice since the fifteenth century, but most have had their original surfaces ‘restored’ to conform to the aesthetic sensibilities of later generations.

The composition of this relief is similar to a terracotta relief in the Galleria dell’Accademia Nazionale di San Luca in Rome, which was attributed to Maini in an inventory of 1830. Jennifer Montagu has shown that Maini’s rectangular relief was adapted as a lunette for the chapel of San Francesco in the right transept of San Andrea delle Fratte (begun 1726; consecrated March 1736).2 It is not clear to which project the present relief relates, but there were other churches dedicated to the saint in Rome, for instance San Francesco di Paola ai Monti.

San Francesco da Paola takes his name from the village in Calabria where he was born in 1416. His parents were Jacopo and Vienna Martotilla. He entered the Franciscan friary of San Marco in Paola as a thirteen-year-old and went on a pilgrimage to Assisi and Rome the following year. On his return to Paola he became a hermit, spending five years in isolation. In 1436, he and two followers established a community which became known as the order of the hermits of St Francis of Assisi. The rule for the order was austere, with an emphasis on penance, humility and charitable works; they eschewed meat. Learning was not considered particularly important and each community usually included only one priest. The order received approval from the Holy See in 1474 and in 1492 Francesco directed that his followers call themselves the Order of Minimi. His reputation for miracle-working and prophecy was such that pope Sixtus IV responded to the request of Louis XI of France in 1483 that Francesco care for him on his deathbed. He remained in France for the rest of his life and Charles VIII and Louis XII endowed monasteries for his order in Pléssis-lez-Tours and Amboise. He died in 1507 at Pléssis. Under the papacy of Leo X, he was beatified on 7 July 1513 and canonized on 1 May 1519.

The prayer book held by the seated angel is open at a page inscribed with part of the collect (short prayer) for his feast day on 2 April 3 – OREMUS deus humilium celsitudo, qui Bea tum Franciscum Confessorem san= ctorum gloria Mast Mi t

Biographical Note:

Monaldi 4 attended the art school run by the Accademia di San Luca in Rome and won prizes in the competitions held there in 1705, 1707, 1709 and 1711. In June 1730 he was admitted to the Academy on condition that he resign from the carpenters’ guild and not serve in public as an artilleryman, i.e. he would be restricted to the Castel Sant’Angelo. Monaldi was appointed by the Academy to supervise the transfer of alcuni gessi (plaster models) which Bernardino Cametti had bequeathed to it in his will.5 He negotiated the rights to all the overspill from a large travertine fountain celebrating Venice’s dominion over the sea, which he had been contracted to make in June 1729 for Palazzo Venezia, Rome, and he used the surplus water to set up washhouses. His earliest marble, a statue of St Francis in the apse of St Peter’s, dates from 1720, and for the same basilica he carved Humility and St Cajetan (latter dated 1730). In the early 1730s he worked on several statues for the basilica built by King Juan V at Mafra in Portugal – three over-lifesize statues of Sts Vincent, Elias and Philip Neri and colossal statues for the exterior of Sts Sebastian and Theresa (latter dated 1731, all five signed).

There followed marble statues of Abundance and Magnificence (1736) for the monument to Clement XII in S. Giovanni in Laterano, Rome; a Pope (1743) in travertine for Santa Maria Maggiore and six stucco reliefs of apostles in the nave of San Marco.

1. We are grateful to Carol Galvin, conservator of sculpture, for providing this visual analysis of the bronzed surface. She has seen other Roman terracottas of the same period with similarly-treated surfaces.

2. J. Montagu in Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, exh. cat. ed. E. P. Bowron & J. J. Rishel, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 16 March – 28 May 2000 & Houston, Museum of Fine Arts, 25 June – 17 September 2000, no. 133, p. 261; V. Golzio, Le terrecotte della R. Accademia di S. Luca, Rome, 1933, pp. 33 & 51, pl. xv. See also J. Montagu, “Giovanni Battista Maini’s role in two sculptural projects: the evidence of the drawings”, “Essays in Memory of Jacob Bean (1923-1992)”, Master Drawings, vol. 31, no. 4, 1993, pp. 454-463, p. 457.

3. Deus, humilium celsitudo, qui beatum Franciscum sanctorum tuorum gloria sublimasti, tribue, quaesumus, ut, eius meritis et exemplo, promissa humilibus praemia feliciter consequamur. We are grateful to Michael Walsh, Theology Librarian, Heythrop College (University of London), for explaining and elaborating these lines in Latin. They may date from the second decade of the sixteenth century, when Francis was beatified and canonised.

4. R. Enggass, Early Eighteenth-century Sculpture in Rome, 1976, pp. 183-188, pls. 188-210

5. Enggass 1976, p. 153.